Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Siblings

Posted : admin On 4/5/2022Wild Bill got his man as usual but accidentally killed a friend during an 1871 Abilene shootout that played havoc with the legendary pistoleer’s mental state.

Martha Jane Cannary-Burke, better known as Calamity Jane (May 1, 1852 – August 1, 1903), was a frontierswoman and professional scout best known for her claim of being a close friend of Wild Bill Hickok, but also for having gained fame fighting Native Americans. While driving cattle to Abilene, Kansas, Hardin killed three Mexican cowboys in June 1871. In Abilene, he briefly became friends with Town Marshal Wild Bill Hickok. Wild Bill had earned a formidable reputation for killings several people. Hardin was proud to be associated with a celebrated gunfighter. He had 7 brothers and sisters: Mabel Laverne Hickok(1914), Marian Ruth Hickok (1916), Kenneth Maurice Hickok (1918), Noel Elmer Hickok (1921), Maizie Mae Hickok (1924), Marie Lavonne Hickok (1926), Wesley Willard Hickok (1929). He married Geneva L. Smith 21 Feb 1931 in Warsaw, Pulaski, Arkansas. He had 1 daughter, Dianna Lavonne Hickok.

About 50 drunken Texas cowboys, deterred by bad weather from attending the Dickinson County Fair, accompanied gambler-cum-saloon owner Phil Coe as he toured the Abilene, Kansas, saloons and got drunker by the hour. It was the evening of October 5, 1871, toward the end of the cattle season, and most of the Texas trail hands had returned home. Many of those who remained were enjoying liquid libations with Coe as he made the rounds on Texas Street. Drunkenness per se did not violate any town ordinance, but Coe and company were armed, and Marshal Wild Bill Hickok, less than six months on his latest lawman job, had warned them against carrying firearms within city limits.

By 9 p.m. the hard-drinking crowd had reached the Alamo Saloon. A gun went off, and the diligent marshal quickly arrived on the scene, demanding to know who had fired the shot. Coe, with six-shooter in hand, said he had shot at a stray dog. To be sure, he was in no mood for a lecture from a lawman he didn’t like. Before the marshal could say another word, Coe pulled a second six-shooter and fired twice at Hickok, one shot striking the sidewalk, the other cutting through the tail of Wild Bill’s coat.

Hickok, “as quick as a thought,” according to a local newspaper, drew his own six-shooters and fired at least three times. Two of the bullets struck Coe in the stomach; the gambler would die in great agony three days later. The third bullet struck an armed man who had run between the two adversaries. Hickok, standing in the glare of kerosene lamps and surrounded by an armed and belligerent crowd, at first could not see who it was. To his horror, he soon discovered he had accidentally shot and killed his friend Mike Williams, who had served on the Abilene police force as a jailer that summer and had planned to leave town that evening to return to his ailing wife in Kansas City. A distraught Hickok (some reports say he was weeping) carried Williams into the Alamo and laid him out on a billiard table.

The gunfight turned out to be Hickok’s last. On December 13, the City Council dismissed the 34-yearold lawman and his deputies. The cattle season was over, and Abilene officials were planning to ban the cattle trade altogether, so the services of a high-priced marshal were no longer needed.

Hickok never wore a badge again. Since he didn’t bother to explain himself, it’s a matter of speculation why he gave up law enforcement. Had he lost his nerve after the accidental shooting of his friend? Or was he merely being prudent because of failing eyesight and a desire to marry and settle down? These questions are open to debate, but one thing is not: James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was a changed man after the shootout at the Alamo Saloon.

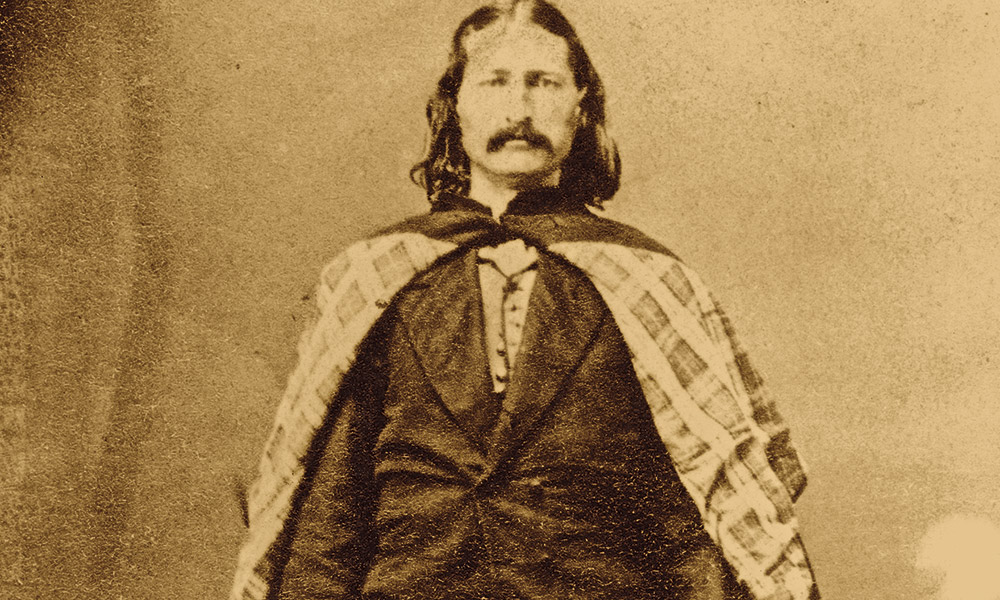

Dubbed “Wild Bill” for his zealous approach to tracking Rebel bushwhackers in Kansas and Missouri as a Union scout during the Civil War, Hickok added to his notoriety as a dead shot and proficient man-killer during various postwar stints as a government detective, scout and courier, deputy U.S. marshal, acting sheriff and town marshal. In those early years, Hickok did nothing to discourage the mythmaking. He was a great leg-puller and storyteller, whose exaggerated accounts of killing hundreds of men surfaced in an 1865 interview at Springfield, Mo., with Colonel George Ward Nichols. That account appeared in the February 1867 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, followed by one with Henry M. Stanley of the Weekly Missouri Democrat. The braggadocio caused many law-abiding citizens to look askance at Hickok and convinced him that pulling the legs of newspapermen was unwise. By 1868 he was refusing to speak to correspondents, but his legend spread anyway.

Aside from the Rebels he allegedly killed during the Civil War, Hickok is known to have fatally shot six men, two in self-defense and the others as a lawman. According to Nichols, when he asked Hickok how killing other men affected him, Wild Bill replied: “I never thought much about it. The most of the men I have killed it was one or t’other of us, and at sich times you don’t stop to think; and what’s the use after it’s all over?” Hickok told Stanley he never killed anyone without good cause, insisting that he didn’t set out to shoot anyone but that sometimes he had no choice; killing was always a last resort.

There was no doubt about Hickok’s skill with the ivory-handled .36-caliber Colt Navies slung from his waist. In a posthumous tribute, a reporter from the Chicago Tribune wrote: “The secret of Bill’s success was his ability to draw and discharge his pistols with a rapidity that was truly wonderful, and a peculiarity of his was that the two were presented and discharged simultaneously, being ‘out and off’ before the average man had time to think about it. He never seemed to take any aim, yet he never missed.”

Some gunmen were better shots than Hickok, his pal Buffalo Bill Cody once said, but few were as adept in the use of a revolver. Wild Bill cocked, aimed and fired as he drew, while most men were inclined to draw, cock and then aim and shoot, which took time.

Pistol prowess aside, Hickok’s strength of character and self-assured appearance enabled him to control others; when they saw the man, they had no reason to doubt the legend. In My Life on the Plains, George Armstrong Custer wrote that Wild Bill’s “influence among the frontiersmen was unbounded; his word was law, and many are the personal quarrels and disturbances which he has checked among his comrades by his simple announcement that ‘this has gone far enough,’” followed by the ominous comment that if they disagreed, they must “settle it with me.”

Few of Hickok’s contemporaries considered him aggressive. But if called upon, he responded without hesitation, accepting full responsibility for his actions. Where others might rely upon brothers or friends for more firepower or backup in gunfights, Hickok did not. When the shooting started, he stood alone.

Even though Hickok stopped tooting his own horn to reporters, there was no shortage of old-timers who claimed to have witnessed Wild Bill’s gunfights. Certainly his performance on the Springfield, Mo., town square on July 21, 1865, was a confrontation observers would long remember and one that would enhance his reputation. A dispute with Davis K. Tutt over a game of cards the previous evening led to a gunfight that was the epitome of the Hollywood-inspired notion of a face-to-face showdown. Some of the so-called eyewitnesses lied about that showdown (their fibs exposed when the coroner’s records were discovered after more than 100 years), but Wild Bill did indeed put a bullet into his adversary’s heart at a range of 75 yards.

Four years later in Hays City, Kan., acting Sheriff Hickok killed trigger-happy Bill Mulvey in August and then shot down saloon rowdy Samuel Strawhun the following month. Hickok’s actions on those occasions met a mixed reception, though he had apparently acted in self-defense. In assessing Hickok’s reputation on November 11, 1869, The Gazette of Delaware, Ohio, stated that he was either “heartily hated” or “more feared than loved.” Hickok lost the November election for sheriff of Ellis County, but that was in part because he was a Republican in a decidedly Democratic community. In July 1870, Hickok was back in Hays City—either for personal reasons or in his capacity as a deputy U.S. marshal— and shot two drunken 7th U.S. Cavalry troopers. It is uncertain how many cavalrymen were present, but Hickok was lucky to escape with his life.

Hickok’s Hays City days were plenty action-packed, but it was in Abilene the following year that his reputation really blossomed. Appointed town marshal, or chief of police, on April 15, 1871, he and several deputies, or constables, were expected to keep the peace and control some 5,000 Texas cowboys who came through Abilene between May and October. In general the lawmen were successful, despite the influx of gamblers, prostitutes and others eager to part the Texans from their money. When the City Council ordered Marshal Hickok to move the undesirables south of the railroad tracks, some referred to the resulting district of brothels and gambling dens as “McCoy’s Addition”—a dig at cattle baron and Mayor Joseph G. McCoy.

Hickok’s October 5 fight with the drunken Phil Coe was the kind of tragedy that was bound to happen sooner or later. Being a lawman in a cow town was dangerous work. Hickok knew this better than anyone. But he met Coe’s challenge and no doubt would have been ready to face similar challenges elsewhere had not his friend Mike Williams walked into the line of fire that night. Afterward, Hickok raged through the streets, disarming would-be troublemakers, and within an hour Abilene was like a ghost town. He insisted on paying for Mike Williams’ funeral and later visited Williams’ widow to express his regret and try to explain how the shooting happened.

Although Hickok was obviously troubled by what had occurred, few residents of Abilene blamed him, and a coroner’s inquest exonerated him. (Records of that inquest and similar records were destroyed by courthouse fires in both Abilene and Hays City.) Some newspapers botched the facts, but the accounts were generally favorable, pointing out that he “bravely did his duty.” Phil Coe, regarded as a thug by some and as a “man of good impulses” by others, got what he deserved, according to the Abilene Chronicle. Some Texans, however, disagreed and were plenty angry. Coe’s family supposedly put a $10,000 price on Hickok’s head. In November five Texans tried to ambush Hickok on a train to Topeka, but he outwitted them and continued, as one news report said, to be a “terror to evildoers.”

Although the Coe fight added to Hickok’s reputation as a gunfighter, he was no longer interested in such accolades. When offered the post of Newton, Kan., city marshal for $200 a month, Wild Bill turned it down, even though he made only $150 a month in Abilene. Had the death of Mike Williams and potential danger to other bystanders deterred him? Perhaps. Even though Hickok knew the killing was an accident, he was in no mental state to jump on another offer to wear a badge. It has been suggested the tragedy broke Hickok’s nerve, but none of his contemporaries believed that. In March 1873, a story circulated that Texans had killed Wild Bill at Fort Dodge, and Hickok finally had to dispel the rumors by writing letters to newspapers, saying he was alive. He did not sound like a man gone timid when he declared, “I never have insulted man or woman in my life, but if you knew what a wholesome regard I have for damn liars and rascals, they would be liable to keep out of my way.”

While Hickok’s nerve might have been intact, his eyesight allegedly had deteriorated and was getting progressively worse. Reports in 1874 suggest he was suffering from an eye disorder induced by the “colored fire” used when he toured with Buffalo Bill’s Combination theater troupe the prior year; later accounts mention successful treatment with “mineral drugs.” But J.W. Buel, in his 1882 book Heroes of the Plains, intimated that following a trip to the Black Hills in late 1875, Hickok sought treatment for “opthalmia” (conjunctivitis) from Kansas City physician Dr. Joshua Thorne. In her book The Buffalo Hunters, Mari Sandoz claims that in the 1930s she discovered a report by the Army surgeon at Camp Carlin, Wyoming Territory, indicating that Hickok had glaucoma and would soon go blind. That report, if it ever existed, has never been located. Camp Carlin was only a remount depot; the nearest surgeon was at Fort D.A. Russell, in Cheyenne, and its records have disclosed nothing. Nevertheless, some modern medical experts have surmised Hickok might have suffered from trachoma, an eye infection that can lead to blindness if not treated.

Whatever the state of Hickok’s vision, after the shootout at the Alamo Saloon he was circumspect about his reputation as a gunfighter. At Cheyenne in 1875, Wild Bill spoke of his burdensome reputation to Annie Tallent, one of the first white women to enter the Black Hills: “I am called a red-handed murderer, which I deny. That I have killed men I admit, but never unless in absolute self-defense, or in the performance of an official duty. I never, in all my life, took any mean advantage of an enemy. Yet understand, I never allowed a man to get the drop on me. But perhaps I may yet die with my boots on.”

By the mid-1870s the Western frontier as Hickok knew it was changing, and he decided it was time to make a new life for himself. Since his youth, he had been romantically linked with a number of women. His first love was Mary Jane, the part-Indian daughter of John Owen, who took him in as a boarder when he arrived at Monticello, Kansas Territory, in 1857. During the Civil War and on the Plains in the late 1860s, Wild Bill had several romantic affairs, including one in Ellsworth, Kan., with “Indian Annie,” who bore him a son that later died. Still, it was not until March 5, 1876, that Bill took the plunge and married. The bride was Agnes Lake Thatcher, a circus performer whose previous husband, Bill Lake, had been murdered some years before. Bill first met Agnes when her circus came to Abilene in 1871, and they were in touch for several years before the wedding.

Marriage to Agnes was meant to presage a new beginning, and Hickok needed money to support his new wife. He reportedly had made a trip to the Black Hills in 1875, and in the spring of 1876 he tried to organize an excursion of would-be gold miners to the hills from St. Louis. Discovering that others had already organized a similar expedition, Hickok put off his plans and went to Cheyenne instead. By the end of June he had joined up with his old friend Colorado Charlie Utter and was on his way to the newly founded mining camp at Deadwood Gulch.

Deadwood seemed the ideal place to make some money at the diggings (as Hickok hinted to his wife in a letter dated July 17 from Deadwood) or perhaps the first step in moving on to somewhere else. Bill told Agnes he wanted to make a home for them, and she intimated in her correspondence with his family at Troy Grove that she was eager to join him. But Hickok did far more gambling than digging, and reports published following his death that August suggested he was not a happy man. Cody, who had met Hickok en route to Deadwood in July, claimed in an interview that September that Wild Bill had said he did not expect to return from the Black Hills.

Even if Hickok’s shooting skills, vision and mental state had been in top form, they would have done him no good when a drifter named Jack McCall walked into Deadwood’s Saloon No. 10 on August 2, 1876, and shot him through the back of the head. Wild Bill was ignominiously denied the opportunity to prove whether he was still the top pistoleer in the West. And now he was dead at age 39.

Wild Bill’s niece Ethel Hickok, who was born in June 1886, almost 10 years after he was murdered, was raised on family lore that emphasized his tender side. In a number of interviews with this author over several years, Ethel said that her father, Horace Hickok, told her Wild Bill disliked his reputation as a man-killer. Ethel recalled that her mother, Martha Edwards Hickok, told her that when stories reached the family concerning his gunfights and the men he was supposed to have killed, Wild Bill’s own mother, Polly, became very upset. According to Ethel, two of the gunfighter’s brothers, Horace and Lorenzo, and his two sisters, Celinda and Lydia, all tried in vain to dispel the false stories.

But even those closest to Wild Bill doubted he ever could have settled down. Ethel said that Lorenzo Hickok, who knew his brother as well or better than anyone, once remarked that if Bill had not died in 1876, his restless spirit and adventurous streak would doubtless have kept him roaming the West. But had he done so, it would likely have been only a matter of time before some other Western ne’er-do-well or hard case took a cheap shot at the onetime lawman and still legendary pistoleer.

English writer and researcher Joseph G. Rosa is the author of many articles and books about Wild Bill Hickok. For suggested reading, try his They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok; Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth; The West of Wild Bill Hickok; and Wild Bill Hickok, Gunfighter: An Account of Hickok’s Gunfights.

Originally published in the December 2008 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.

Who was Wild Bill Hickok?

Did Wild Bill Hickok Have Siblings Died

Wild Bill Hickok was an American folk hero. His exploits as a gunfighter, scout, and lawman were legendary and he became the topic of many fictionalized accounts.

He was born James Butler Hickok on 27 May 1837 in Troy Grove, Illinois. His parents were William Alonzo Hickok and Polly Butler.

Duck Bill and Shanghai Bill

Prior to the Civil War, Wild Bill claims he was called Shanghai Bill, but because of his big nose and a protruding upper lip, some of his enemies referred to him as Duck Bill. He is said to have started calling himself Wild Bill by 1861 and by 1869 newspapers were referring to him as Wild Bill as well.

Dead Man’s Hand

In 1876 at a saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota, Jack McCall snuck up behind Wild Bill and shot him with a single bullet to the back of the head. Wild Bill was playing poker at the time and never knew what hit him. Much later it was reported that the hand he held at the time of his murder was a pair of black aces and a pair of black eights. The fifth card is unknown. This has become known as 'The Dead Man’s Hand'.